PALMEHUSET

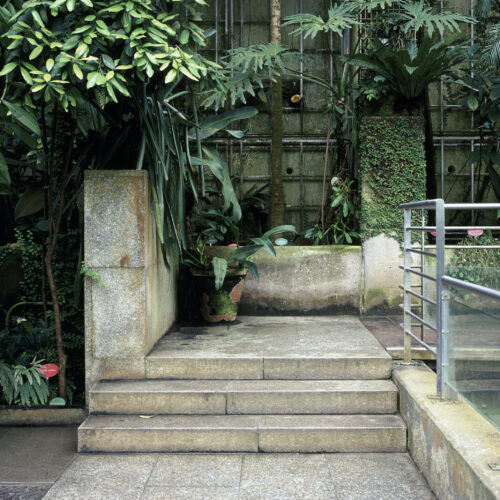

Palmehuset significa “casa de palmeras” en danés. Este trabajo, que comenzó en Noruega, en el jardín botánico de Bergen, es un recorrido entre lo calido y lo gélido, entre lo salvaje y lo estructurado, entre la libertad y el orden más minucioso. Pero también son imágenes que muestran el poder de adaptación, la convivencia y la supervivencia. Palmehuset es una serie de casas de palmeras en ciudades europeas, principalmente del Norte de Europa: Bergen, Oslo, Copenhague, Londres, Edimburgo, Lyón, Viena, Salzburgo, Ámsterdam, Berlín, Frankfurt, Lisboa y Madrid. En mi trabajo, en el que muestro series de lugares, se repiten los esquemas de aquello en lo que se deposita la mirada. Estos invernaderos ubicados dentro de jardines botánicos evocan tiempos pasados en los que se conservaban especies de otros mundos muy lejanos como grandes joyas vivientes. Toda gran familia entre los siglos XVIII y XIX poseía su “Jardín de las Delicias” como un lujo exótico. El jardín botánico se mantiene como una isla dentro de las urbes modernas con su ritmo frenético.

Siempre viene una estructura dada. Una especie de “piel” que actúa como contenedor de esa Naturaleza artificialmente mantenida. Estas arquitecturas especialmente diseñadas para el engaño de la propia Naturaleza se convierten en lugares de protección. Espacios que nos dan las claves para la adaptación a la realidad cambiante y disfrazada, al mismo tiempo que proponen una ética coyuntural.

En las casas de Palmeras también existe egoísmo, egoísmo por el espacio y por la luz. La luz es, en estas parcelas, la que da la vida- igual que en la fotografía- a cada una de las especies que se empujan hacia lo ancho y hacia arriba, quizá para huir y volver a sus selvas de origen. Las hojas se expanden y las flores se abren de manera casi agresiva dentro de estas jaulas de cristal que las estructuran, las ordenan y las archivan. En realidad, nos encontramos entre esa lucha por la búsqueda de libertad de lo natural, de lo salvaje, del origen y, por otro lado, la estructura creada por el hombre que no nos deja salir de lo establecido, lo artificial, un límite ya dibujado. Sin embargo, en estos lugares apaciguados, parece que esta lucha se transforma en una convivencia, donde las tuberías se convierten en raíces, los colores se funden en verdes y tierras y el óxido de los metales se envuelve en verdín. La estructura de hierro, que contiene esta naturaleza imparable, se vuelve poco a poco orgánica, pero sólo hacia sus interiores, sólo sus tripas respiran el oxigeno de las plantas, hacia fuera permanece inmóvil, fuerte, fría pero magnánima.

Quizá esta controversia de las diferentes batallas libradas no nos lleve a ningún sitio, como los pasillos que aparecen repetidos hacia ningún lugar. Es esa línea disipada que crea una escisión entre lo natural y lo artificial. En realidad, mi mirada en Palmehuset pretende mostrar que si hay lucha es por algo a lo que no se puede renunciar, por la supervivencia de nuestras creencias, por la libertad a la que estamos destinados, por la búsqueda de nuestro origen vinculado al orden natural de las cosas, un orden universal. Algunas especies con más fuerza, otras desde los suelos de tierra o de baldosas, pero todas crecen, evolucionan y en ese camino crean formas maravillosas y únicas, como mostraba el Bosco en su “Jardín de las Delicias”.

PALMEHUSET

Palmehuset is Danish for “palm house”. This work, which started life in the Bergen botanical garden in Norway, is a journey between heat and ice cold, between wildness and structure, between total freedom and painstaking order. But its images also illustrate the power of adaptation, coexistence and survival. Palmehuset is a series of palm houses in European – mainly north European – cities: Bergen, Oslo, Copenhagen, London, Edinburgh, Lyon, Vienna, Salzburg, Amsterdam, Berlin, Frankfurt, Lisbon and Madrid. The project is a succession of schemes, each one representing the object of an observer’s gaze. These greenhouses set in botanical gardens recall past times when species from other, faraway worlds were kept like great living treasures. Between the 18th and 19th centuries, every important family possessed its own “Garden of Delights” as an exotic luxury. Today, botanical gardens still survive, like islands amid the frenzied rhythm of modern cities.

A certain structure is always there, a “skin” of sorts acting as a container for the artificially conserved Nature within. These architectures, especially designed to trick Nature itself, become protection zones, spaces that show us how it is possible to adapt to changing, disguised reality while at the same time proposing a conjunctural ethical code.

In palm houses there is also selfishness, an avidity for space and light. In these places, as in photography, light is what gives life to each of the species that push themselves upwards and sideways, perhaps in an attempt to escape and return to their forests of origin. Leaves expand and flowers bloom almost aggressively inside these glass cages where they are structured, arranged and catalogued. In fact, we find ourselves caught up in a struggle between natural, wild, original elements seeking their freedom and a man-made structure that will not allow us to break away from the established rules, from this artificial world with its pre-defined boundaries. In such peaceful settings, however, the struggle seems to turn into coexistence: pipes and tubes become roots, colours melt into greens and ochres and rusting metal is clad in green. The iron structure enclosing this unstoppable natural life force slowly becomes organic, but only inwardly. Only its bowels breathe in the plants’ oxygen. Outwardly, it remains lifeless, strong, cold and yet majestic.

Perhaps this discrepancy, these different battles being fought, are pointless, like repeated paths leading nowhere. But it is that hazy line that creates a split between the natural and the artificial worlds. My intention in Palmehuset is really to show that if a struggle exists, it is for something that we cannot renounce: for the survival of our beliefs, the liberty for which we are destined, the quest to find an origin that links us to the natural order of things, a universal order. All species grow and evolve, some more forcefully than others and some from the soil on the floor or between paving stones. And as they do so, they create marvellous, unique forms, reminiscent of those Hieronymus Bosch painted in his “Garden of Earthly Delights”.